A brief history of the drum machine

Creativity, innovation and technology have walked hand-in-hand through the history of music - sometimes creeping, sometimes leaping – shaping the sound of albums, genres and whole eras in the process.

によって Anton Spice

2024年8月29日

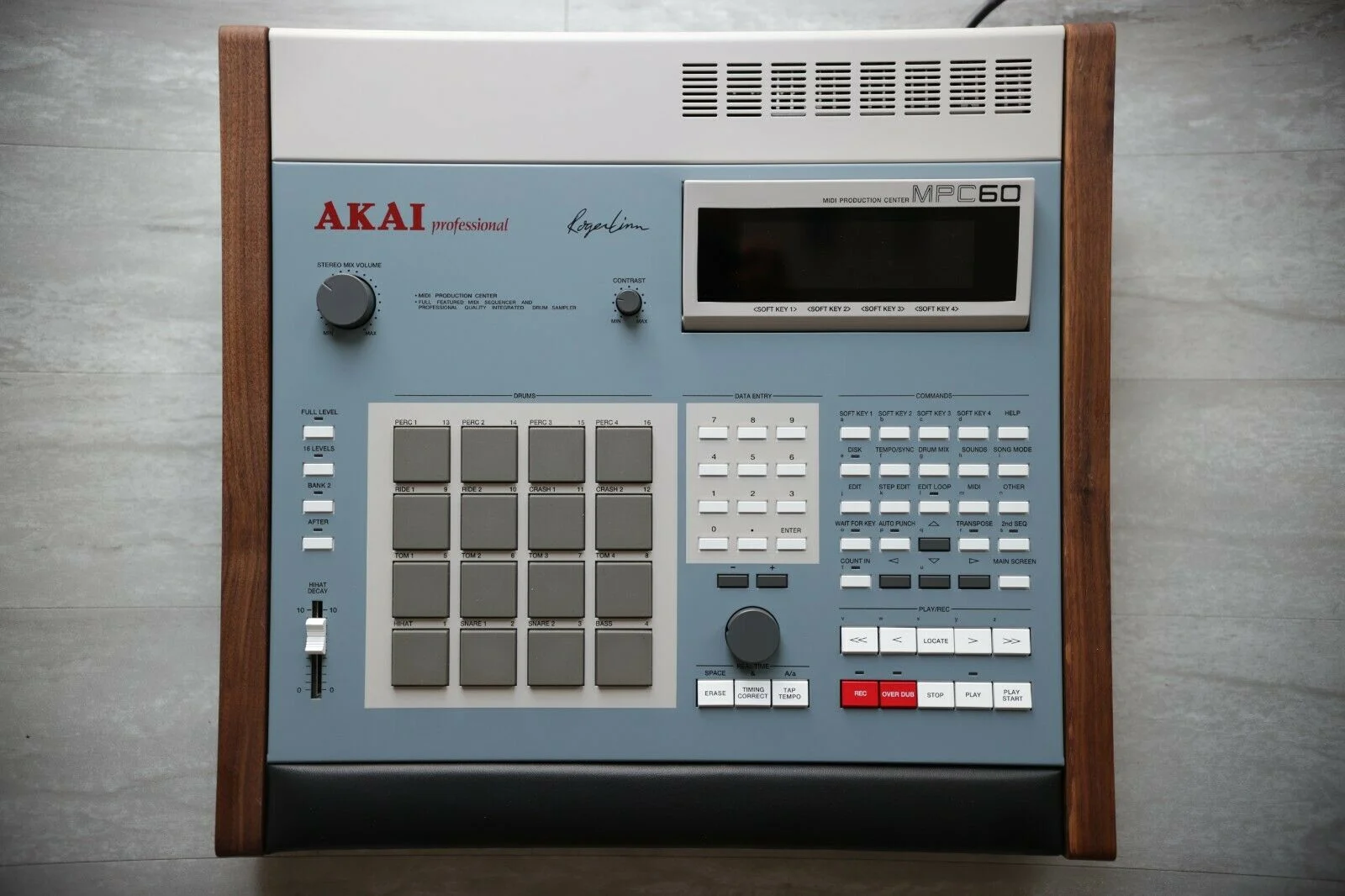

“People have been making music for a long time, with sticks and with skins, with bows and with strings. Our need to create has not changed, but technology has continued to evolve. Technology has just taken a giant leap forward.” These are the words of electronic instrument designer Roger Linn, introducing the game-changing Akai MPC-60 sampler from a corporate living room straight out of 1988. It may seem odd to start a history of the drum machine in the middle, but Linn’s words speak to something bigger than the MPC. Creativity, innovation and technology have walked hand-in-hand through the history of music - sometimes creeping, sometimes leaping – shaping the sound of albums, genres and whole eras in the process. And while the 1980s may be the decade most synonymous with the drum machine as iconic models such as the Roland TR-808, TR-909 and Linn LM-1 defined the new sound of pop, hip-hop, house and techno, it was fifty years earlier that the modern history of the electronic rhythm instrument really began.

Forward-thinking composers were flirting with mechanisation as an aesthetic or compositional device.

In 1930, American composer Henry Cowell invited Russian inventor Léon Theremin (of the Theremin fame) to build a machine capable of producing pitched polyrhythmic patterns which he called the Rhythmicon. Played via a keyboard that used photoelectric technology, the Rhythmicon could produce 16 patterns - an experiment in sequential sound from a time when forward-thinking composers were flirting with mechanisation as an aesthetic or compositional device. Only three Rhythmicons were ever made, and reviews were not particularly warm. Even one of Cowell's associates, the conductor Nicholas Slominsky, had his reservations. “Like many a futuristic contraption, the Rhythmicon was wonderful in every respect,” Slominsky wrote some years later, “except that it did not work.”

That it would be over twenty-five years before the next development in drum machine technology says a lot about just how much of an outlier the Rhythmicon was. What it did do however, was to set a precedent for instruments whereby a single motion, such as the pressing of a key, could activate a sequence of sounds – a paradigm shift the significance of which was, in its own way, seismic. Made for a completely different audience – family singalongs rather than avant garde symposiums – the Chamberlin Rhythmate was developed in 1957 by Iowa engineer Harry Chamberlin, complete with 14 pre-recorded tape loops of drum beats that could be sped up or slowed down depending on the mood of the occasion. Only 100 Rhythmate’s were produced, but two years later, the world would finally have its first consumer drum machine - a chunky wooden number called the Wurlitzer Side Man that functioned like a giant music box, playing a selection of pre-set rhythms such as ‘waltz, ‘samba’ and ‘cha cha’ for pub singers and lounge pianists to tootle along to.

‘The Rhythmicon’ set a precedent for instruments where the pressing of a key could activate a sequence of sounds.

While it could be called a drum machine insofar as it was capable of playing percussive loops and patterns, you’d be hard pressed to call the Side Man an instrument. In the 1960s, this reliance on pre-sets did however became more sophisticated, giving rise to subsequent products like the Thomas Band Master Model 55, housed in a rather smart wooden suitcase and with options like ‘Clave’, ‘Drum Roll’ and ‘Brush Cymbal’, and inventor Raymond Scott’s homespun machines like the Rhythm Synthesizer and somewhat awkwardly titled Bandito the Bongo Artist, which featured on his now cult album of bedtime electronica, Soothing Sounds for Baby.

Meanwhile, over in Japan, things were beginning to get interesting. Determined to make a better drum machine than the Wurlitzer Side Man, engineering graduate and accordion player Tadashi Osanai co-founded Keio-Giken (which later became Korg) to make two Donca-Matic instruments in the early 1960s, before alighting on the Keio-Giken Mini Pops Jr. which was small enough to play on a desk. In the same breathe, watch and clock enthusiast Ikutaro Kakehashi was channelling his fascination with mechanical time into the 1967 Ace Tone FR-1 Rhythm Ace, an instrument significant in so far as it gave Kakehashi a taste of how much was still to be done. Five years later he would go on to found the Roland Corporation and write arguably the most significant chapter in the history of drum machines. But we’re not quite there yet.

Sly Stone’s ‘Family Affair’ became the first number one hit in the world to feature a drum machine.

Towards the end of the 1960s, a step change began to occur in the use of drum machines in music production. No longer just rhythm boxes or novelty accompaniments, musicians looking for a new palette of sounds were reaching for mechanised beats even if they were not yet able to programme them. Dating from 1969, the Italian-made Elka Drummer One became a favourite among German electronic musicians such as Cluster and Kraftwerk. In the United States, soul innovator Sly Stone dubbed the Maestro Rhythm King MRK-2 his “funk box”, using it extensively on classic 1971 album There’s A Riot Goin’ On. When lead single ‘Family Affair’ reached the top of the US charts in November of that year, it became the first number one hit in the world to feature a drum machine. Things were about to change, and change fast.

It was with the advent of programmable drum machines that the instruments most people associate with the technology were born. But as we have seen on this journey so far, the first iteration of a piece of technology was rarely the one that stuck around the longest. And so it was with the Eko ComputeRyhthm, an early programmable drum machine also made in Italy in 1972. Although it ended up on records by Jean-Michel Jarre and Manuel Göttsching, fewer than twenty were ever sold and as such it has become one of the rarest and most expensive units in the drum machine story.

The CR-78 allowed musicians to write, play, save and then replay rhythms.

It would be six years until, in 1978, Roland entered the market for real with the cube-like CR-78, primitive in comparison to subsequent models, but a first for being based on a microprocessor, allowing musicians to write, play, save and then replay rhythms. “As soon as you hear that wonky, clattering metal beat, you’re right into an alternative sonic universe,” Ultravoxx’s John Foxx has said of the CR-78. “I came to understand that its rigidity forces you to work in certain ways and I like that. Its very limitations would give me ideas.” Other notable fans included Phil Collins (‘In the Air Tonight’), Blondie (‘Heart Of Glass’), Hall & Oates (‘I Can’t Go For That’) and Tears For Fears (‘Mad World’), all of whom contributed to cementing the drum machine in pop music lore.

But then came 1980. In a single year, three iconic machines – the Linn LM-1, Oberheim DMX and Roland TR-808 were introduced, although their impact would be felt in different ways. Where Roland’s TR-808 continued to create percussive sounds from analogue synthesis as the CR-78 had done, the Linn and Oberheim models were the first to use digital sampling, opening up a whole new world in the process.

Let’s begin with Roger Linn. An engineer with a musician’s mind, Linn had been dissatisfied with the sound of most commercial drum machines which he famously once said “sound like crickets”. And as far as Linn and many of his contemporaries in the late 1970s were concerned, that a drum machine didn’t sound an awful lot like a real drummer was something of a drawback. To remedy this, the Linn LM-1 was the first drum machine to use 8-bit samples of acoustic drums. With timing correction and shuffle features, users could tweak the feel of their patterns, raising its appeal with professional studios not least because, retailing at $5,000, the Linn LM-1 was out of the reach of most consumers. Widely adopted by everyone from Peter Gabriel to Stevie Wonder, it was in Prince’s hands that the creative potential of the Linn LM-1 was fully realised. By the time the follow up LinnDrum was introduced in 1982, its thick snare and kick sounds were all over the charts in the US, and driving the Japanese anime soundtracks of Izumi ‘Mimi’ Kobayashi.

The DMX had a whole host of flair additions such as flams and rolls to make it feel even more like a real drummer.

Another model that entered the digital sampling market was the Oberheim DMX, developed to challenge the success of the Linn LM-1 at a slightly more accessible (albeit still hefty) price. The DMX had 24 individual drum sounds born from 11 samples, and a whole host of flair additions such as flams and rolls to make it feel even more like a real drummer. This attention to realism, still clunky by today’s standards, meant that the Oberheim DMX appealed to emerging hip-hop producers, who favoured a more organic drum sound, although the eagle-eared will also hear it on New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’ and The Police’s ‘Every Breath You Take’.

And yet, while Linn and Oberheim pursued sample-based drum realism, it was the Roland TR-808 Rhythm Composer that would arguably have the biggest impact of all. The first of its kind to allow users to programme a percussion track in its entirety, it was limitations in memory that encouraged Ikutaro Kekehashi and his colleagues to rely instead on synthesis or “transistor rhythms” (from which the TR in TR-808 took its name). As synth-based drum machines go, the TR-808 was still as good as they got in 1980, but somehow fell flat between a studio market that wanted real drums and a consumer market not able to see its creative possibilities. Echoing Linn’s crickets, it was once described somewhat obscurely as sounding like “marching anteaters”.

"The TR-808 was the rock guitar of hip-hop." — Questlove

One artist who wasn’t perturbed by its vermilinguan qualities was Ryuichi Sakamoto, who incorporated the TR-808 into the Yellow Magic Orchestra sound early on. Afrika Bambaataa & The Soulsonic Force’s ‘Planet Rock’ was another early example of the 808 in action, as musicians looking to add a futuristic sheen to their productions found in the 808 a sonic aesthetic that would lay the foundations for contemporary hip-hop. Before long everyone from Whitney Houston to Run-DMC and Public Enemy were making magic with the humble Roland, whose sound continues to run like a thread through contemporary hip-hop and dance music. The Roots’ drummer Questlove went so far as to say that the 808 was “the rock guitar of hip-hop”, and as such one of most influential instruments in music, regardless of genre.

Not to be outdone, Roland’s follow up the TR-909 would shake things up once more. But once again, it would take a commercial failure to bring it to life. Introduced in 1983, it was the first Roland machine to incorporate digital samples and the first anywhere to add MIDI functionality. Discontinued and picked up for peanuts in the thrift stores from the Bronx in New York to Chicago and Detroit, the TR-909 packed more of a punch than its predecessor and appealed to producers like Frankie Knuckles and Mr Fingers, whose primary concerns were rooted squarely on the dancefloor. As house flourished in Chicago, artists like Jeff Mills in Detroit were beginning to write the TR-909 into techno history too.

The TR-909 was the first Roland machine to incorporate digital samples, and the first anywhere to add MIDI functionality.

If there is a parable to be drawn from both the TR-808 and 909 it’s that technological development was not as linear as a simple history might make it seem. That two of the least commercially successful devices would become the most influential perhaps says more about human creativity than it does about the instruments themselves. It was never just about the machine; it was also about how you used it.

And so we arrive where we began and the Akai MPC-60, developed by Linn with the Japanese Akai organisation – a MIDI production centre, sampler and sequencer that allowed users to record and programme their own drum sounds and play them from 16 responsive pad controllers, inspired in part by Linn’s own discontinued Linn9000 device. Designed to challenge the dominance of E-Mu Systems’ Drumulator, SP-12 and SP1200 samplers, the versatility of the MPC-60 quickly cornered the hip-hop market, both responding to and driving the proliferation of sample-based music. DJ Shadow’s 1996 album Endtroducing was recorded entirely on the MPC-60, while later models such as the MPC3000 became the machine of choice for J Dilla who disabled the quantize feature to develop his own swung “Dilla time” style, which remains unsurpassed.

For Linn, the Akai MPC-60 may have represented “a giant leap forward”, but as the resurgence, recycling and reapplication of classic drum machines continues to show, music doesn’t mind leaping backwards either. That the Rhythmicon was used by electronic experimentalist Joe Meek in the 1960s, TR-808 was repurposed by UK ravers 808 State at the end of 1980s, the TR-909 featured on Björk’s 1997 track ‘Hunter’, and the MPC was integrated into Theo Parrish and Moodymann’s loose house sound in the 2010s suggests that at every stage, drum machines tended to outlive their eras. And often it was their imperfections - that most human of all characteristics - that appealed most.

The introduction of the MPC-60 in 1988 was not the end of the story. Models from Korg, E-Mu and others began to predict the in-the-box workflows of DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations) such as FruityLoops (now FL Studio), Native Instruments and Ableton, which would themselves have an impact on the sound of more contemporary genres such as grime.

As the need for stand-alone drum machines was replaced, so has an interest in analogue synthesis returned.

But as we’ve seen, nothing about this is entirely linear. As the need for stand-alone drum machines was replaced by more integrated systems, and digital software emulators created facsimile sound banks of classic beats, so has an interest in analogue synthesis returned, and since the early 2010s, Korg, Akai and Roland have all revisited the market, joined by boutique and pocket-sized instruments made by the likes of Teenage Engineering. Almost one hundred years on, it’s just possible Henry Cowell and Léon Theremin would have been rather impressed.